By 2050, the global population is projected to reach 9.8 billion people, doubling the demand for food. However, expanding farmland to meet this need is unsustainable. Over 50% of new cropland created since 2000 has replaced forests and natural ecosystems, worsening climate change and biodiversity loss.

To avoid this crisis, scientists are turning to plant breeding—the science of developing crops with higher yields, disease resistance, and climate resilience. Traditional breeding methods, however, are too slow to keep up with the urgency of the problem.

This is where drones and artificial intelligence (AI) are stepping in as game-changers, offering a faster, smarter way to breed better crops.

Why Traditional Plant Breeding Is Falling Behind

Plant breeding relies on selecting plants with desirable traits, such as drought tolerance or pest resistance, and cross-breeding them over multiple generations. The biggest bottleneck in this process is phenotyping—the manual measurement of plant characteristics like height, leaf health, or yield.

For example, measuring plant height across a field of 3,000 plots can take weeks, with human errors causing inconsistencies of up to 20%. Additionally, crop yields are improving at just 0.5–1% annually, far below the 2.9% growth rate needed to meet 2050 demands.

Maize, a staple crop for billions, illustrates this slowdown: its annual yield growth has dropped from 2.2% in the 1960s to 1.33% today. To bridge this gap, scientists need tools that automate data collection, reduce errors, and speed up decision-making.

How Drone Technology Is Transforming Plant Breeding

Drones, or Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), equipped with advanced sensors and AI, are revolutionizing agriculture. These devices can fly over fields and collect precise data on thousands of plants in minutes, a process known as High Throughput Phenotyping (HTP).

Unlike traditional methods, drones capture data across entire fields, eliminating sampling bias. They use specialized sensors to measure everything from plant height to water stress levels.

For instance, multispectral sensors detect near-infrared light reflected by healthy leaves, while thermal cameras identify drought stress by measuring canopy temperature.

By automating data collection, drones reduce labor costs and accelerate breeding cycles, making it possible to develop improved crop varieties in years instead of decades.

The Science Behind Drone Sensors and Data Collection

Drones rely on a variety of sensors to gather critical plant data. RGB cameras, the most affordable option, capture visible light to measure canopy cover and plant height. In sugarcane fields, these cameras have achieved 64–69% accuracy in counting stalks, replacing error-prone manual counts.

Multispectral sensors go further by detecting non-visible wavelengths like near-infrared, which correlate with chlorophyll levels and plant health. For example, they have predicted drought tolerance in sugarcane with over 80% accuracy.

- RGB Cameras: Capture red, green, and blue light to create color images.

- Multispectral Sensors: Detect light beyond the visible spectrum (e.g., near-infrared).

- Thermal Sensors: Measure heat emitted by plants.

- LiDAR: Uses laser pulses to create 3D maps of plants.

- Hyperspectral Sensors: Capture 200+ light wavelengths for ultra-detailed analysis.

Thermal sensors detect heat signatures, identifying water-stressed plants that appear hotter than healthy ones. In cotton fields, thermal drones have matched ground-based temperature measurements with less than 5% error.

LiDAR sensors use laser pulses to create 3D maps of crops, measuring biomass and height with 95% precision in energy cane trials. The most advanced tools, hyperspectral sensors, analyze hundreds of light wavelengths to spot nutrient deficiencies or diseases invisible to the naked eye.

These sensors helped researchers link 28 new genes to delayed aging in wheat, a trait that boosts yields.

From Flight to Insight: How Drones Analyze Crop Data

The drone phenotyping process begins with careful flight planning. Drones fly at 30–100 meters altitude, capturing overlapping images to ensure full coverage. A 10-hectare field, for instance, can be scanned in 15–30 minutes.

After the flight, software like Agisoft Metashape stitches thousands of images into detailed maps using Structure-from-Motion (SfM)—a technique that converts 2D photos into 3D models. These models allow scientists to measure traits like plant height or canopy cover at the tap of a button.

AI algorithms then analyze the data, predicting yields or identifying disease outbreaks. For example, drones scanned 3,132 sugarcane plots in just 7 hours—a task that would take three weeks manually. This speed and precision enable breeders to make faster decisions, such as discarding low-performing plants early in the season.

Key Applications of Drones in Modern Agriculture

Drones are being used to tackle some of farming’s biggest challenges. One major application is direct trait measurement, where drones replace manual labor. In maize fields, drones measure plant height with 90% accuracy, cutting errors from 0.5 meters to 0.21 meters.

They also track canopy cover, a metric indicating how well plants shade the ground to suppress weeds. Energy cane breeders used this data to identify varieties that reduce weed growth by 40%.

Another breakthrough is predictive breeding, where AI models use drone data to forecast crop performance. For instance, multispectral imagery has predicted maize yields with 80% accuracy, outperforming traditional genomic testing.

Drones also aid in gene discovery, helping scientists locate DNA segments responsible for desirable traits. In wheat, drones linked canopy greenness to 22 new genes, potentially boosting drought tolerance.

Additionally, hyperspectral sensors detect diseases like citrus greening weeks before symptoms appear, giving farmers time to act.

Boosting Genetic Gains with Precision Technology

Genetic gain—the annual improvement in crop traits due to breeding—is calculated using a simple formula:

(Selection Intensity × Heritability × Trait Variability) ÷ Breeding Cycle Time.

Genetic gain (ΔG) is calculated as:

ΔG = (i × h² × σp) / L

Where:

- i = Selection intensity (how strict breeders are).

- h² = Heritability (how much of a trait is passed from parents to offspring).

- σp = Trait variability in a population.

- L = Time per breeding cycle.

Why It Matters: Drones improve all variables:

- i: Scan 10x more plants, allowing stricter selection.

- h²: Reduce measurement errors, improving heritability estimates.

- σp: Capture subtle trait variations across entire fields.

- L: Cut cycle time from 5 years to 2–3 years via early predictions.

Drones enhance every part of this equation. By scanning entire fields, they let breeders select the top 1% of plants instead of the top 10%, increasing selection intensity. They also improve heritability estimates by reducing measurement errors.

For example, manually assessing plant height introduces 20% variability, while drones cut this to 5%. Moreover, drones capture subtle trait variations across thousands of plants, maximizing trait variability.

Most importantly, they shorten breeding cycles by enabling early predictions. Sugarcane breeders using drones have tripled their genetic gains compared to traditional methods, proving the technology’s transformative potential.

Overcoming Challenges and Embracing the Future

Despite their promise, drone-based phenotyping still faces significant challenges. The high cost of advanced sensors remains a major barrier – hyperspectral cameras, for example, can exceed $50,000, making them unaffordable for most small-scale farmers.

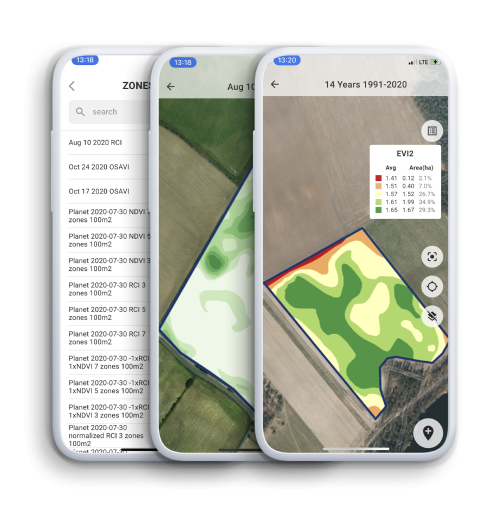

Processing the massive amounts of data collected also requires substantial cloud computing resources, which adds to the expense. AI platforms like AutoGIS are automating data analysis, eliminating the need for manual input.

Researchers are also integrating drones with soil sensors and weather stations, creating a real-time monitoring system that alerts farmers to pests or droughts. These innovations are paving the way for a new era of precision agriculture, where data-driven decisions replace guesswork.

Conclusion

Drones and AI are not just transforming plant breeding—they’re redefining sustainable agriculture. By enabling faster development of drought-resistant, high-yield crops, these technologies could double food production by 2050 without expanding farmland.

This would save over 100 million hectares of forests, equivalent to the size of Egypt, and reduce the carbon footprint of farming. Farmers using drone data have already cut water and pesticide use by up to 30%, protecting ecosystems and lowering costs.

As one researcher noted, “We’re no longer guessing which plants are best. The drones tell us.” With continued innovation, this fusion of biology and technology could ensure food security for billions while safeguarding our planet.

Reference: Khuimphukhieo, I., & da Silva, J. A. (2025). Unmanned aerial systems (UAS)-based field high throughput phenotyping (HTP) as plant breeders’ toolbox: a comprehensive review. Smart Agricultural Technology, 100888.

Crop monitoring