Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) is a critical concept in modern agriculture, playing a pivotal role in enhancing plant growth and optimizing overall crop yield. As the global population continues to rise, the demand for food production intensifies, making it imperative for farmers to adopt sustainable and efficient farming practices.

Nutrients are essential for plant growth, development and metabolism. They play important roles in various physiological processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, enzyme activity, cell division, signal transduction and stress response.

Plants require different amounts and types of nutrients depending on their species, growth stage and environmental conditions. Some nutrients are needed in large quantities (macronutrients), such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) etc. Others are needed in small quantities (micronutrients), such as iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu) etc.

What is Nutrient Use Efficiency?

It refers to the ability of a plant to utilize nutrients effectively for its growth and development. In simpler terms, it is a measure of how efficiently plants absorb and utilize essential elements from the soil, water, and air.

Its use involves minimizing losses and maximizing the uptake and utilization of nutrients by plants, ultimately contributing to improved crop performance. It can be expressed as the ratio of plant biomass or yield to nutrient uptake or input.

A high NUE means that plants produce more biomass or yield with less nutrient uptake or input, while a low NUE means that plants require more nutrients to achieve the same level of growth or production.

Furthermore, NUE can be defined in different ways depending on the question being asked and the data available. Some common terms used to express NUE are:

- Partial factor productivity (PFP): the amount of crop yield per unit of applied nutrient

- Agronomic efficiency (AE): the increase in crop yield per unit of applied nutrient

- Partial nutrient balance (PNB): the amount of nutrient uptake per unit of applied nutrient

- Apparent recovery efficiency (RE): the difference in nutrient uptake between fertilized and unfertilized crops per unit of applied nutrient

- Internal utilization efficiency (IE): the amount of crop yield per unit of nutrient uptake

- Physiological efficiency (PE): the increase in crop yield per unit of difference in nutrient uptake between fertilized and unfertilized crops

Global Response to Its Importance

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global fertilizer consumption has increased by more than 500% since 1961, reaching more than 200 million tonnes of nutrients in 2023. This has contributed to a significant increase in crop production and food availability, but also to a large amount of nutrient losses to the environment.

Further, the FAO estimates that only 42% of nitrogen (N) and 15% of phosphorus (P) applied as fertilizers are taken up by crops globally, while the rest is lost through leaching, runoff, erosion, volatilization, denitrification, or immobilization.

Therefore, the FAO has set a target to increase the global average NUE from 42% to 52% by 2030. This would require reducing N fertilizer use by 20% while increasing crop N uptake by 10%. Similarly, the Scientific Panel on Responsible Plant Nutrition has proposed a vision for achieving nature-positive plant nutrition by 2050. This vision includes five aims:

- Halving nutrient waste along the food system through responsible consumption, increased recycling, and better management practices.

- Soil nutrient depletion and carbon loss halted, leading to improved soil health and organic matter.

- Nutrient losses to water bodies reduced by 75%, preventing eutrophication and algal blooms.

- Nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture reduced by 50%, contributing to mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

- Crop yields and quality increased by 50%, enhancing food security and nutrition.

The global average NUE of cereals was 33%, of oilseeds was 48%, of roots and tubers was 62%, of pulses was 64%, of fruits was 66%, of vegetables was 68%, and of sugar crops was 69% in 2018/19.

In China, a large-scale participatory experiment involving more than 20 million farmers showed that reducing N fertilizer application by an average of 14% increased wheat yield by an average of 10%, resulting in an increase of Partial Factor Productivity by an average of 29%.

While, in India, a field experiment involving different rice varieties showed that applying site-specific nutrient management based on soil testing increased grain yield by an average of 17%, Resource Efficiency by an average of 22%, and Profitability per Nutrient Balance by an average of 28%, compared to farmers’ practice .

Similarly, In Kenya, a field experiment involving different maize-legume intercropping systems showed that applying micro-doses of fertilizer along with organic manure increased grain yield by an average of 79%, Agronomic Efficiency by an average of 86%, Resource Efficiency by an average of 51%, and Profitability per Nutrient Balance by an average of 50%, compared to sole cropping with no fertilizer.

These examples demonstrate the potential of improving NUE through various strategies and practices that can enhance crop production while reducing nutrient losses and emissions.

How It is Important in Plant Growth?

NUE is important for both economic and environmental reasons, as it can reduce the cost of crop production and the risk of nutrient losses to the environment. However, here are some major aspect of plant growth which are highly linked to it.

1. Enhanced Photosynthesis

One of the main factors that NUE affects is photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert light energy into chemical energy. Photosynthesis depends on the availability of nutrients, especially nitrogen (N), which is a key component of chlorophyll, the pigment that absorbs light.

N also plays a role in the synthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and other molecules that are essential for plant growth and development. Phosphorus is also essential for energy transfer, while potassium regulates the opening and closing of stomata, influencing carbon dioxide uptake.

Therefore, efficient nutrient utilization directly impacts the rate of photosynthesis, leading to increased energy production for plant growth.

2. Cellular Structure and Function

Another factor that it affects is cellular structure and function, which determines how nutrients are taken up, transported, stored, and utilized within the plant cells. Cellular structure and function depend on the availability of nutrients, especially phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) etc.

For instance, calcium is involved in cell wall development, ensuring cell integrity and strength. Magnesium is a central component of chlorophyll molecules, supporting photosynthesis. Hence, efficient nutrient use ensures the proper functioning of cells and tissues, promoting overall plant health.

3. Resistance to Stress and Diseases

A third factor that it affects is resistance to stress and diseases, which can reduce plant growth and yield by affecting various physiological and biochemical processes. Stress and diseases can be caused by various factors, such as drought, salinity, temperature extremes, nutrient deficiency or toxicity, pests, pathogens, weeds, etc.

Therefore, adequate nutrient supply strengthens plants, making them more resilient to environmental stresses and diseases. Well-nourished plants can better withstand adverse conditions, such as drought or pest attacks. Furthermore, nutrient-efficient plants exhibit improved stress tolerance, contributing to sustained growth and higher crop yields under challenging circumstances.

What Factors Affect It and How to Control Them?

NUE in agriculture is not a one-size-fits-all concept; rather, it is influenced by a variety of factors that intricately shape the way plants absorb, utilize, and respond to essential nutrients. The factors that influence it include soil properties, climate conditions, crop species and varieties, management practices, and interactions among these factors.

1. Soil Properties

Soil properties, such as texture, structure, pH, organic matter, and microbial activity, have a significant impact on NUE. Soil texture and structure affect the water holding capacity, aeration, drainage, and root penetration of the soil.

These factors influence the availability and mobility of nutrients in the soil solution and the uptake by plant roots. For example, sandy soils have low water holding capacity and high leaching potential, which can reduce the NUE of nitrogen (N) and potassium (K).

Clayey soils have high water holding capacity and low aeration, which can limit the NUE of phosphorus (P) and micronutrients.

Furthermore, soil pH affects the solubility and availability of nutrients in the soil. Most nutrients are more available in slightly acidic to neutral soils (pH 6-7), while some micronutrients, such as iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), are more available in acidic soils (pH < 6).

Soil organic matter and microbial activity influence the cycling and transformation of nutrients in the soil. Organic matter provides a source of carbon (C) and energy for soil microorganisms, which can mineralize organic forms of nutrients into inorganic forms that are available for plant uptake.

Microorganisms can also immobilize nutrients by incorporating them into their biomass or by forming complexes with organic molecules.

2. Climate Conditions

Climate conditions, such as temperature, rainfall, solar radiation, and wind, affect NUE through their effects on soil processes, plant growth, and nutrient losses. Temperature affects the rate of chemical and biological reactions in the soil, as well as the metabolic activity and development of plants.

Higher temperatures generally increase the mineralization of organic matter and the availability of nutrients in the soil, but they can also increase the volatilization of ammonia (NH3) from urea or manure applications, or the denitrification of nitrate (NO3-) into nitrous oxide (N2O) or dinitrogen (N2) gases.

Higher temperatures can also accelerate plant growth and nutrient demand, but they can also reduce plant water uptake and transpiration, which can affect nutrient transport within the plant.

Similarly, rainfall affects the water balance and nutrient dynamics in the soil-plant system. Adequate rainfall is essential for maintaining soil moisture and nutrient availability for plant uptake, but excess rainfall can cause leaching or runoff of nutrients from the soil surface or subsurface layers.

Rainfall can also influence the timing and frequency of irrigation and fertilizer applications, which can affect NUE. Solar radiation affects the photosynthetic activity and biomass production of plants, which determine their nutrient demand and uptake.

Furthermore, wind also affects NUE by influencing soil erosion, evaporation, and volatilization processes. Wind can cause soil erosion by detaching and transporting soil particles that contain nutrients from one place to another.

Wind can also increase evaporation from the soil surface or plant canopy, which can reduce soil moisture and nutrient availability for plant uptake.

3. Plant Characteristics and Varieties

Crop species and varieties differ in their genetic potential for NUE, as well as their response to environmental and management factors. Some crops have higher inherent NUE than others due to their physiological traits, such as root morphology, nutrient uptake kinetics, translocation efficiency, assimilation capacity, remobilization efficiency, harvest index, etc.

For example, cereals generally have higher NUE than legumes due to their higher harvest index (the ratio of grain yield to total biomass) and lower nutrient concentration in their grains.

Furthermore, crop varieties within a species may also vary in their NUE due to genetic trait differences or breeding efforts. For example, some rice varieties have higher NUE than others due to their ability to use alternative sources of nitrogen (N), such as ammonium (NH4+) or atmospheric N2 fixation by symbiotic bacteria.

Some wheat varieties have higher NUE than others due to their ability to use phosphorus (P) more efficiently by secreting organic acids or phosphatases that solubilize P from the soil. Some maize varieties have higher NUE than others due to their ability to use potassium (K) more efficiently by reducing K leakage from the roots or by increasing K uptake under low K availability.

4. Management Practices

Management practices, such as tillage, crop rotation, intercropping, cover cropping, irrigation, fertilization, weed control, pest control, and harvest management, can affect NUE by modifying the soil environment, the crop growth, and the nutrient losses.

Tillage

Tillage affects the physical and biological properties of the soil, such as soil structure, organic matter, microbial activity, and nutrient distribution. It can improve NUE by increasing soil aeration and drainage, which can enhance nutrient availability and uptake by plant roots.

However, it can also reduce NUE by increasing soil erosion and nutrient losses, or by decreasing soil organic matter and microbial activity, which can reduce nutrient cycling and availability.

Crop Rotation

Crop rotation emerges as a strategy to improve NUE by diversifying nutrient demand and supply among crops. Beyond nutrient considerations, it also proves effective in breaking pest and disease cycles, thereby contributing to enhanced NUE.

For example, rotating cereals with legumes can improve NUE by increasing the N supply from biological N2 fixation by legumes, or by reducing the N demand of cereals due to their lower N requirement.

Intercropping

Intercropping, involving the simultaneous cultivation of two or more crops on the same piece of land, is celebrated for its positive impact on NUE. It achieves this by fostering complementarity and synergy among crops for nutrient use. For instance, intercropping cereals with legumes alters N supply patterns, positively influencing NUE.

Cover Cropping

Cover cropping, a practice involving the growth of a crop between two main crops to cover the soil surface and prevent erosion, offers dual impacts on NUE. On one hand, it positively contributes by boosting NUE through increased organic matter, microbial activity, and nutrient cycling.

On the other hand, challenges arise as cover crops may compete for nutrients, water, and light, potentially impacting NUE.

Irrigation

Irrigation, when applied judiciously, improves NUE by maintaining optimal soil moisture and nutrient availability. However, poorly executed irrigation may reduce NUE through nutrient leaching or runoff.

Fertilization

Fertilization, if appropriately timed and applied, enhances NUE by increasing nutrient availability for plant roots. Nevertheless, excessive applications may lead to nutrient losses, underscoring the delicate balance in fertilization practices.

Weed Control

Weed control improves NUE by reducing nutrient competition and losses due to weeds. However, its impact on soil properties must be carefully considered, as it may influence N availability and uptake.

Pest Control

Pest control positively impacts NUE by reducing nutrient losses due to pest damage. Yet, similar to weed control, its influence on soil properties may affect nutrient availability and cycling.

Harvest Management

Harvest management, involving decisions regarding when and how to harvest crops, plays a crucial role in influencing NUE. Positively, it enhances NUE by optimizing yield and reducing nutrient concentration in harvested parts. However, inadequate harvest management may leave behind nutrients in residual parts, impacting NUE.

What are The Major Indicators of NUE for Different Systems?

It measures how well a cropping system uses the available nutrients to produce crops. However, NUE is not a simple or uniform indicator. It can vary depending on the inputs and outputs considered, the scale and boundaries of the system, and the purpose of the assessment. Therefore, it is important to use appropriate indicators that reflect the goals of responsible plant nutrition.

Fertilizer Indicators

These indicators focus on the efficiency of nutrient utilization from fertilizers. They show how effectively applied nutrients are converted into crop yield, which can inform decisions on optimal nutrient management and resource allocation. Some of the common fertilizer indicators are:

1. Partial factor productivity (PFP): This is the ratio of crop yield to fertilizer nutrient applied. It indicates the productivity per unit of fertilizer input. A high PFP means a high yield with low fertilizer input. However, it does not account for other sources of nutrients or losses to the environment.

For instance, in well-taken-care-of cereal crops, the PFP usual range for grain yield per kilogram of applied nitrogen is 50 to 100 kilograms.

2. Agronomic efficiency (AE): This is the increase in crop yield per unit of fertilizer nutrient applied. It indicates the marginal return of fertilizer input. A high AE means a large yield increase with low fertilizer input. However, it does not account for the initial soil fertility or losses to the environment.

Taking nitrogen as an example, in cereal systems that are well taken care of, the AE is typically around 20-30 kilograms of grain per kilogram of nitrogen applied. However, it can sometimes be even higher than that.

3. Recovery efficiency (RE): This is the fraction of fertilizer nutrient applied that is taken up by the crop. It indicates the effectiveness of nutrient uptake from fertilizers. A high RE means a low loss of fertilizer to the environment. However, it does not account for the yield or quality of the crop.

For example, according to a global analysis by Zhang et al. (2015), the average PFP, AE, and RE of nitrogen (N) fertilizers for cereal crops were 42 kg grain/kg N, 15 kg grain/kg N, and 0.33 kg N uptake/kg N applied, respectively. These values varied widely across regions and crops, reflecting differences in soil conditions, climate, cropping systems, and management practices.

Crop Indicators

These indicators define the allocation of nutrients within a plant and its impact on crop yield and quality. They show how efficiently a crop uses the absorbed nutrients to produce biomass or economic products. Some of the common crop indicators are:

1. Nutrient harvest index (NHI): This is the ratio of nutrient content in harvested parts to total aboveground nutrient uptake. It indicates the proportion of absorbed nutrients that are allocated to economic products. A high NHI means a high nutrient removal with harvest and a low nutrient return to soil.

Typical NHI values in maize have been documented within the range of 59-70% for nitrogen (N), 79-91% for phosphorus (P), and 13-19% for potassium (K) (13). Similarly, in rice, reported ranges include 54-65% for N, 61-71% for P, and 12-19% for K.

2. Internal efficiency (IE): This is the ratio of crop yield to nutrient content in harvested parts. It indicates the efficiency of economic product formation per unit of removed nutrient. A high IE means a high yield with low nutrient concentration in harvested parts.

For instance, improvements in maize breeding have raised nitrogen use efficiency from 45 kg per kg of nitrogen uptake in 1946 to 66 kg/kg in 2015.

3. Physiological efficiency (PE): This is the ratio of crop yield to nutrient content in aboveground biomass. It indicates the efficiency of economic product formation per unit of total plant nutrient content. A high PE means a high yield with low nutrient concentration in biomass.

4. Nutrient concentration (NC): This is the amount of nutrient content per unit of dry matter in harvested parts or aboveground biomass. It indicates the quality or nutritional value of the crop product or residue.

Further, according to a meta-analysis by Dobermann (2007), the average NHI, IE, PE, and NC values for N in cereal crops were 0.67 kg N/kg N uptake, 90 kg grain/kg N in grain, 134 kg grain/kg N in biomass, and 1.5% N in grain, respectively.

System Indicators

These indicators consider the whole cropping system, including the soil, the crop, and the environment. They show how efficiently a system uses the available nutrients from all sources and minimizes the losses to the environment. Some of the common system indicators are:

1. System boundary NUE (SB-NUE): This is the ratio of total N output to total N input within a defined system boundary. It indicates the overall N balance of the system. A high SB-NUE means a high N output with low N input. However, it does not account for the spatial and temporal variability of N flows within the system.

2. Partial nutrient balance ratio (NUEPB): This is the difference between fertilizer nutrient input and nutrient output in harvested parts. It indicates the net change in soil nutrient status due to fertilization. A positive PNB means a surplus of fertilizer nutrient in the soil, while a negative PNB means a deficit. Global NUEPB averages, inclusive of fertilizer, manure, fixation, and deposition, show increases to 55% for nitrogen and 77% for phosphorus.

For most cereals, like wheat and corn, the natural process of getting nitrogen (N) from the air (biological fixation) is usually not a lot, less than 10 kilograms per hectare. But for crops like rice and sugarcane, it can be a bit more, around 15-30 kilograms per hectare.

And for some legumes, such as soybeans, peanuts, pulses, and forage legumes, it can be even higher, ranging from 100 to 300 kilograms per hectare. Sometimes, when we water the plants (irrigation), it also brings in some nutrients, which can be important in specific situations.

3. Farm-gate nutrient balance ratio (NUEFG)

It extends the system boundary beyond the soil surface, considering farms with integrated crop and animal production. Livestock inclusion often reduces NUEFG due to additional complexities. Improving NUEFG involves optimizing nutrient use across the entire farm, managing manure, and minimizing external nutrient inputs.

Expanding the boundary further, Food Chain Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUEFC) assesses nutrient availability for human consumption relative to the total nutrient input in the entire food system. For nitrogen, NUEFC estimates range from 10% to 40% among European countries. However, due to the complexity of the food production chain, practical applications and meaningful assessments remain challenging.

4. Nutrient surplus (NS): This is the difference between total nutrient input and total nutrient output within a defined system boundary. It indicates the potential loss of nutrient to the environment. A high NS means a high risk of environmental pollution.

For examples, according to a global analysis by Lassaletta et al. (2014), the average SB-NUE, PNB, and NS values for N in crop production were 0.42 kg N/kg N input, 65 kg N/ha, and 65 kg N/ha, respectively.

How to Improve Nutrient Use Efficiency For Better Outcomes?

Responsible plant nutrition is a strategy to ensure food security and environmental protection by optimizing the use of nutrients in agricultural systems. Therefore, it is important to monitor and assess NUE using appropriate tools that can capture its complexity and variability. Here are some important methods that can help farmers and researchers improve NUE in responsible plant nutrition.

1. Nutrient Testing

Nutrient testing is a method of measuring the nutrient status of soil and plant tissue samples. It can provide valuable information on the availability and uptake of nutrients in the soil-plant system, as well as the potential for nutrient losses or deficiencies. Nutrient testing can help farmers and researchers to:

- Identify the optimal type, rate, timing, and placement of nutrient inputs, such as fertilizers, manure, irrigation water, etc.

- Evaluate the agronomic and economic performance of different nutrient management practices, such as crop rotation, intercropping, cover cropping, etc.

- Detect and correct nutrient imbalances or disorders that may affect crop yield and quality, such as nitrogen deficiency, phosphorus toxicity, micronutrient deficiency, etc.

- Monitor the environmental impact of nutrient inputs, such as leaching, runoff, volatilization, greenhouse gas emissions, etc.

Nutrient testing can be done using various methods, such as soil testing kits, portable sensors, laboratory analysis, etc. However, nutrient testing is not a one-time activity. It should be done regularly and frequently to capture the dynamic changes in nutrient status throughout the cropping season and across different fields.

2. Remote Sensing and Technology

Remote sensing is a technique of collecting data from a distance using devices such as satellites, drones, cameras, etc. It can provide spatially and temporally continuous information on various aspects of crop growth and development, such as biomass production, leaf area index, chlorophyll content, water stress, etc. Remote sensing can help farmers to:

- Estimate the crop yield potential and variability across different fields or regions

- Assess the crop response to different nutrient inputs or management practices

- Detect and diagnose nutrient deficiencies or stresses that may affect crop growth and quality

- Optimize the timing and rate of nutrient applications based on crop demand

- Reduce the cost and labor of field sampling and testing

Remote sensing can be done using various platforms and sensors, such as optical, thermal, radar, hyperspectral, etc. However, remote sensing is not a standalone tool. It should be calibrated and validated using ground-truth data from field measurements or nutrient testing.

3. Crop Modeling

Crop modeling is a method of using mathematical equations to describe and predict the behavior of crops under different conditions. It can provide quantitative information on the interactions between crops, nutrients, soil, water, climate, and management practices. Crop modeling can help to:

- Understand the underlying mechanisms and processes that affect NUE in crops

- Evaluate the effects of different scenarios or interventions on NUE outcomes

- Optimize the design and implementation of field experiments or trials

- Extrapolate or upscale the results from field measurements or remote sensing to larger scales or regions

Crop modeling can be done using various types of models, such as empirical, mechanistic, or hybrid models. However, crop modeling is not a simple tool.

It requires a lot of data and expertise to calibrate and validate the models and to interpret the results correctly. Moreover, crop modeling should be used in conjunction with other tools such as nutrient testing or remote sensing to verify and complement the model outputs.

How GeoPard Can Help in Improving Nutrient Use Efficiency?

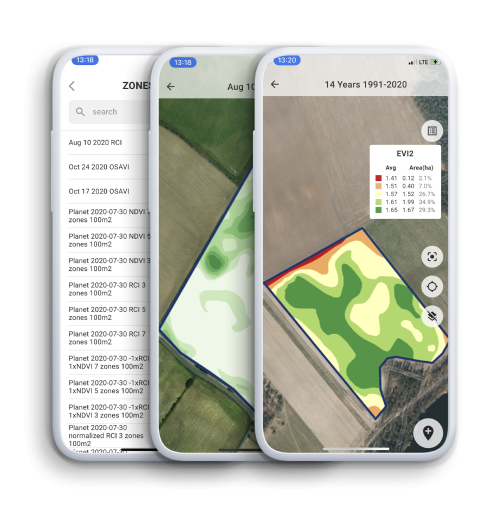

In the pursuit of sustainable and responsible plant nutrition, the role of advanced technologies is becoming increasingly vital. GeoPard, a cutting-edge platform specializing in precision agriculture, offers a suite of services designed to improve Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) through soil data analytics, nutrient testing, and smart scouting.

1. Soil Data Analytics

GeoPard’s soil data analytics feature provides a detailed map of soil properties, facilitating the creation of prescription maps for Variable Rate Application (VRA) fertilization. This capability allows farmers to:

- Optimize Fertilization: Tailor fertilizer application to specific soil characteristics, preventing over-fertilization and reducing environmental impact.

- Delineate Management Zones: Compare soil characteristics with other layers and generate variable rate fertilizer prescription files for efficient nutrient distribution.

- Plan Soil Sampling: Strategically plan soil sampling points based on multi-year zones, reflecting historical crop development patterns.

It further excels in enhancing plant nutrition efficiency through its suite of services. It simplifies soil data interpretation with easy-readable heatmap visualizations, enables precise fertilizer application through Variable Rate Application (VRA) Fertilization, and provides reliable insights into soil conditions with high-density soil scanners.

Additionally, It ensures accurate nutrient plan implementation, monitors As-Applied & As-Planted Data, and offers valuable 3D maps and topography analytics for enhanced decision-making by growers. In essence, GeoPard is a powerful solution for streamlined and sustainable plant nutrition management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Nutrient Use Efficiency (NUE) plays a pivotal role in the global agricultural landscape, and its importance in promoting optimal plant growth cannot be overstated. As we recognize the multifaceted factors influencing NUE and the diverse indicators across various systems, the need for strategic interventions becomes apparent.

GeoPard emerges as a key player in this endeavor, offering innovative solutions to enhance NUE. By leveraging its user-friendly features, such as easy-readable heatmap visualizations and precision-driven Variable Rate Application (VRA) Fertilization, it empowers farmers to make informed decisions and streamline nutrient management practices.

Precision Farming