Soil sampling is a critical process in agriculture, geotechnical engineering, and environmental management because it provides the basic data on soil condition and quality needed for decision making. It informs farmers about nutrient levels, helps engineers design stable foundations, and allows scientists to monitor contamination.

In practice, vast areas are sampled: for example, China’s recent national soil survey covered about 730 million hectares and collected over 3.11 million soil samples. This reflects the scale of global soil monitoring efforts. In fact, the global soil testing equipment market was valued at around $5.52 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow roughly 10.4% per year through 2030.

However, not all soil samples are collected the same way. The method used can preserve the soil’s natural structure (an undisturbed sample) or mix it (a disturbed sample), and this choice greatly affects what tests can be done on the sample.

Disturbed Soil Sampling

Soil investigations worldwide heavily rely on disturbed samples because they are inexpensive and quick to obtain. According to agricultural surveys, over 80% of farm soil tests in North America and Europe are based on disturbed composite samples, while in construction, disturbed split-spoon samples are part of more than 90% of geotechnical site investigations. This widespread use highlights their practicality in large-scale projects.

A disturbed soil sample is one where the soil’s original structure or moisture regime has been altered during collection. In other words, the layers may have collapsed or mixed, and the particles are no longer in their in-situ arrangement. This type of sample is acceptable when only the soil’s basic composition is needed.

For example, disturbed samples are used for chemical analyses (nutrients, pH, contaminants) and classification tests (grain-size distribution, Atterberg limits). Once mixed, the sample gives accurate results for these properties even though structural details are lost.

Common disturbed-sampling techniques include hand augers, bucket augers, shovels, and split-spoon samplers. These methods are simple, low-cost, and quick. For instance, a hand or power auger (a screw drill) is twisted into the ground and soil cuttings are periodically brought up.

The soil removed (often from a shallow depth) can be collected in a container for analysis. Auger drilling is typically used for disturbed samples in shallow investigations (up to ~20 feet deep). The cuttings from the auger are often mixed together to form a bulk sample. This is a rapid way to collect material for nutrient testing or basic soil classification when detailed layering information is not needed.

Another very common disturbed method is the split-spoon sampler (used in the Standard Penetration Test, SPT). A split-spoon is a hollow steel tube driven into the ground by repeated hammer blows. After each 6-inch drive, the number of blows (the “N-value”) is recorded as an indication of soil compactness. When the sampler is withdrawn, the core of soil inside is removed and split open for examination.

The extracted sample is disturbed (it has been hammered and scrapped out of the hole), but it provides good qualitative information on grain size, moisture content, and consistency. Split-spoon samples are widely used on construction sites and environmental assessments because they provide both a disturbed soil sample and an in-situ density index (blow count).

Split-spoon (SPT) sampling uses a hollow tube hammered into the soil to collect a disturbed core and measure resistance. It is widely used in geotechnical and environmental field investigations for soil classification and density testing.

Disturbed sampling is also standard in agriculture and pollution surveys. Farmers typically collect many small cores (using a soil probe or auger) from different parts of a field and mix them into a composite sample for laboratory analysis. For example, one guideline recommends taking 15–20 soil cores per 4–5 hectares of field and combining them into a single mixed sample.

That sample is then tested for pH and nutrient levels to guide fertilization. Similarly, when testing for contaminants, multiple cores across the site may be composited so the lab analysis represents the area. Because the samples are mixed, precise layering or structure is irrelevant for these tests.

The main advantages of disturbed sampling are cost, speed, and simplicity. Little equipment is needed and many samples can be taken quickly. This makes it ideal for large-scale surveys and preliminary screenings. The limitations are that no information about in-situ density, strength, or compaction can be obtained from such samples.

You cannot use a disturbed sample to measure shear strength or settlement. In short, disturbed sampling is best when chemical or classification data is needed, but it cannot support tests of the soil’s natural mechanical or hydraulic behavior.

Undisturbed Soil Sampling

With the global push for safer infrastructure, undisturbed soil sampling has become a standard in major construction projects. For instance, in 2022, more than 65% of infrastructure projects in Asia-Pacific included undisturbed Shelby tube or piston sampling as part of their ground investigation. The demand for accurate geotechnical data is also fueling the growth of advanced samplers, with the market for high-precision soil coring tools expected to grow by over 8% annually through 2030.

An undisturbed soil sample is obtained with minimal alteration so that the soil’s original fabric, stratification, and moisture remain intact. This involves specialized techniques and tools. Undisturbed samples are required when measuring properties that depend on the soil’s structure (e.g. shear strength, compressibility, hydraulic conductivity). By keeping the sample essentially “as it was in the ground,” the laboratory tests will reflect real field conditions.

The most common tool for undisturbed sampling is the thin-walled Shelby tube (also known as a push tube or Acker tube). A Shelby tube is a steel cylinder, typically 2–3 inches in diameter and 24–30 inches long, with one sharp end. It is pushed (often hydraulically) into the soil to capture a core.

Because the wall is thin, the cutting edge shears off a cylinder of soil with minimal disturbance. After penetration, the tube is carefully extracted; the soil core inside comes out largely intact. The tube is then sealed (with a cap or wax) to preserve moisture and structure. The extracted core can be transported to a lab for testing.

Thin-walled Shelby tubes are pushed into clay or silt layers to recover nearly undisturbed soil cores for lab tests. Each core is sealed immediately after retrieval to maintain its natural moisture and structure.

Other undisturbed methods include piston samplers and block sampling. A piston sampler works by driving a tube into the soil with a piston inside to prevent suction and disturbance. Block sampling involves cutting out a large cube of soil (rarely used, due to difficulty) to get a fully intact block. The goal of all these methods is to minimize disturbance: the sampler moves steadily and cleanly, avoiding jolts and vibration that could disturb the soil fabric.

Undisturbed samples are used for laboratory tests that cannot tolerate disturbance. Common tests include triaxial shear tests (for strength), oedometer consolidation tests (for settlement), and constant-head or falling-head permeability tests (for flow). For example, a Shelby tube sample of clay will be tested under controlled stress to see how it compresses, which is critical for predicting foundation settlement.

The advantages of undisturbed sampling are accuracy and completeness for engineering properties. An intact sample gives reliable data on how soil will behave in its natural state. The limitations are that it is costly, complex, and sometimes impractical. Drilling rigs and trained operators are needed.

The process is slower, and there is a risk of losing the sample if it crumbles. Even so-called undisturbed samples can acquire some disturbance if not collected properly; this is why careful techniques and standards are critical.

Role of Precision Agriculture in Disturbed vs. Undisturbed Soil Sampling

Precision Agriculture (PA) is fundamentally changing how we collect and utilize soil data, optimizing both disturbed and undisturbed sampling methods for unprecedented efficiency and insight. By integrating advanced sensors, data analytics, and targeted sampling strategies, PA addresses the traditional trade-offs between cost, scale, and accuracy.

Disturbed Sampling: Speed, Scale & Automation

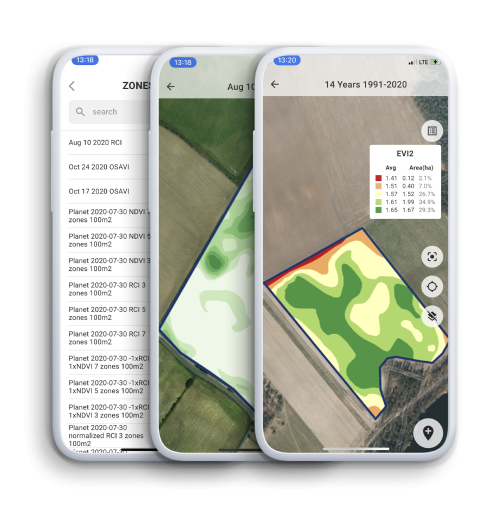

1. Targeted Grids/Zones: PA uses satellite imagery, yield maps, and EM soil sensors to create management zones. Instead of uniform grids (e.g., 1 sample/acre), sampling density drops 50-70% while maintaining or improving accuracy. Farmers sample only key zones, saving time and lab costs.

2. Automation: Robotic soil probes (e.g., Agrowtek, FarmDroid) autonomously collect disturbed samples at predefined points. This slashes labor costs by up to 50% and enables high-frequency monitoring impractical manually.

3. On-the-Go Analysis: Mounted NIR/PXRF sensors on tractors or UTVs provide instant disturbed soil analysis for pH, organic matter (OM), and key nutrients (K, P) in the field, enabling real-time decisions.

Undisturbed Sampling: Precision Placement & Viability

1. Pinpointing Critical Areas: PA identifies high-value or problematic zones (e.g., compaction hotspots via yield maps + penetrometer data, potential contamination areas via historical data) where undisturbed sampling’s cost is justified. Drones with LiDAR or thermal cameras further refine these targets.

2. Guided Extraction: GPS-guided hydraulic coring rigs ensure precise placement of Shelby tubes or piston samplers exactly where needed for critical shear strength or hydraulic conductivity tests, maximizing data value per sample.

3. Reducing “Disturbance”: Technologies like sensor-feedback during coring (monitoring insertion force/vibration) help minimize unintended disturbance, improving sample quality for lab analysis.

Disturbed vs. Undisturbed Soil Sampling Analysis with GeoPard

Modern soil sampling is no longer just about collecting dirt from the ground—it’s about precision, efficiency, and accuracy. This is where GeoPard Agriculture plays a vital role.

By combining advanced algorithms, smart path planning, and zone-based intelligence, GeoPard ensures that both disturbed and undisturbed soil sampling are carried out in a way that saves time, reduces cost, and maximizes data quality. GeoPard supports both grid-based and zone-based sampling strategies.

1. Grid-Based Sampling is useful for disturbed samples in fields where no prior data exists. It divides the land into equal cells and ensures that soil is sampled systematically across the entire area. This provides a solid baseline for nutrient analysis, especially in new fields.

2. Zone-Based Sampling leverages field variability data such as yield maps, satellite imagery, and soil maps. This method is particularly effective when dealing with undisturbed sampling, where soil structure and physical properties must be preserved from representative zones. By focusing only on distinct areas of variability, it avoids unnecessary disturbance and captures meaningful soil differences.

Furthermore, GeoPard allows users to define label templates for each sampling point, whether disturbed or undisturbed. This improves lab processing and ensures that results are easy to trace back to exact field locations. Organized labeling also reduces errors and helps generate clearer reports for decision-making. Meanwhile, GeoPard offers multiple options for point placement within zones:

- Smart Sampling Recommendation (recommended): Uses AI to optimize point placement, adapting density based on variability. More points are taken in variable areas, fewer in uniform areas. This is especially valuable when sampling disturbed soils for fertility mapping.

- Core Line Logic: Places points along straight transect lines, ideal for machinery-based sampling and for creating consistent undisturbed cores that reflect natural soil layering.

- N/Z Logic and W Logic: These zigzag or back-and-forth patterns ensure coverage across irregular or elongated zones. This is helpful for both disturbed and undisturbed samples, especially in fields where soil transitions or compaction issues need to be monitored.

Why GeoPard Matters for Disturbed vs. Undisturbed Sampling?

- For disturbed samples, GeoPard ensures that sampling is representative, systematic, and cost-effective. Farmers get precise nutrient maps that power variable-rate fertilization and reduce input costs.

- For undisturbed samples, GeoPard helps identify the most critical zones for careful extraction, making sure that compaction, porosity, and hydraulic properties are assessed where they matter most.

Tip: For first-time soil sampling, GeoPard recommends using its Smart Sampling Recommendation. The system automatically adapts to the unique characteristics of each field, ensuring a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Choosing a Soil Sampling Method

Globally, around 70% of routine soil tests rely on disturbed samples, but when safety or structural integrity is involved, undisturbed methods dominate. For example, more than 80% of highway and bridge projects in the U.S. and Europe specify undisturbed sampling in their geotechnical contracts. This shows that method choice is not only technical but also tied to regulations and risk management.

The decision between disturbed and undisturbed sampling depends on the project goals, the soil type, and practical constraints. In general:

1. Sampling Objective: If you only need chemical or grain-size information (for example, soil fertility or basic classification), a disturbed sample is sufficient. If you need mechanical or hydraulic properties (strength, compressibility, permeability), you must collect undisturbed samples.

For example, a foundation design study needs data on clay compressibility, so engineers would use Shelby tubes or piston samplers to get intact cores. If the goal is simply to measure nutrient content, a quick auger sample will do.

2. Soil Conditions: Cohesive soils (clays, silts) often require undisturbed sampling to preserve their structure. In contrast, very loose sands or gravels may be difficult to sample intact (the hole tends to collapse). In such cases, engineers may rely on split-spoon samples or perform in-situ tests instead.

3. Depth and Access: Deep sampling or hard layers may only be accessible with heavy equipment. If only shallow samples are needed, hand tools may suffice. Conversely, collecting an undisturbed core from deep ground water often requires large-diameter drilling, which may not be possible on tight budgets.

4. Cost and Time: Disturbed methods are low-cost and fast. An auger or split-spoon rig can rapidly collect many samples. Undisturbed methods are high-cost and slow (equipment rental, labor). This must be balanced against project needs. For example, a large-scale fertilizer survey might use only disturbed samples for speed, whereas a high-value construction project will invest in undisturbed coring for safety.

5. Regulatory Requirements: Sometimes regulations dictate the sampling method. For instance, regulations for ground-water monitoring often require undisturbed sampling for permeability tests. In practice, if testing standards (ASTM, EPA, etc.) call for a “thin-walled tube sample,” then that method must be used.

In summary, match the method to the property of interest: use disturbed sampling when only composition matters, and undisturbed sampling when in-situ structure matters.

Applications of Disturbed And Undisturbed Soil Sampling

The importance of soil sampling is reflected in sector-specific demand. The global agricultural soil testing market exceeded $2.6 billion in 2023, while geotechnical testing contributed heavily to the construction sector’s growth, with investments in soil sampling services increasing by over 12% annually in developing countries. Environmental testing, particularly for contamination, is expected to rise significantly due to stricter regulations.

1. Agriculture: Soil sampling for farming typically focuses on fertility (chemical composition) and rarely requires preserving soil structure. Agronomists usually collect many shallow cores across a field (often 15–30 cores per field or 4–5 hectares) and combine them into a composite sample.

A clean bucket or probe collects soil (usually from 0–15 cm depth) from each point, and these subsamples are mixed in one container. That mixture is sent to a lab to test pH, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, etc. The composite approach averages out small-scale variability. The tools are often simple probes or augers and the samples are inherently disturbed, but that is acceptable for chemical tests.

Agricultural soil sampling often uses probes or augers to take many small cores across a field, then mixes them into one composite sample for nutrient analysis.

2. Geotechnical Engineering: Design of foundations, embankments, and pavements requires knowledge of soil strength and deformation. This usually mandates undisturbed sampling (especially in fine-grained soils). In a typical geotech investigation, drillers may alternate between disturbed and undisturbed samplers in the same boring.

For example, in a clay layer they might first drive a split-spoon sampler to get a disturbed sample for Atterberg limits and grain size, and then drive a thin-walled Shelby tube to get an undisturbed core for consolidation and shear tests. The tube cores will then be tested for properties like compressibility and bearing strength, while the spoons are used for classification.

In sandy soils, engineers may rely more on SPT samples (since Shelby tubes don’t work well in loose sand) or use vibracoring to get relatively undisturbed samples if needed.

3. Environmental Investigation: Environmental projects often use a mix of methods. When mapping contamination, technicians commonly collect disturbed auger samples or hand-auger borings at many locations to test for pollutant concentrations. These samples can be quickly obtained and give the concentration of chemicals in the soil.

However, if the study involves understanding how contamination moves (e.g. leaching through soil into groundwater), undisturbed samples are needed to measure permeability or sorption. In practice, a site investigation might use disturbed sampling for basic screening and then one or more undisturbed cores for in-depth hydraulic or mechanical testing.

Challenges and Best Practices

Soil sampling errors cost industries significant money. A recent estimate suggested that poor sampling and handling can lead to up to 25% data inaccuracy, resulting in unnecessary fertilizer costs for farmers and potential safety risks in geotechnical projects. As a result, stricter adherence to best practices has become a focus, with modern labs reporting that quality-controlled undisturbed cores improve reliability of strength testing by over 30% compared to poorly handled samples.

Collecting high-quality soil samples requires careful attention to avoid unintentional disturbance and to preserve the sample. Even an “undisturbed” sample can be compromised if it is shaken or allowed to dry. To minimize disturbance, drillers use slow, steady techniques: for example, pushing a Shelby tube at a constant rate with hydraulic pressure, or using a piston to gently advance a sampler.

Vibration and rapid withdrawal should be avoided in sensitive soils. Standard procedures (e.g. ASTM methods) often specify filling samples slowly to prevent washing away fines or creating pressure changes.

Once collected, preserving the sample is crucial. An undisturbed core must be sealed immediately to keep its moisture and structure. The common practice is to cap and seal the ends of a tube core (often with metal end caps or wax) as soon as it is out of the ground. This prevents water from evaporating and the core from cracking.

The sealed sample is then stored upright or properly supported and transported to the lab. If undisturbed samples are shipped upright in a rigid sleeve, their orientation (vertical axis) is kept the same for testing.

Disturbed samples (bulk or composite) should be placed in clean, airtight bags or containers once collected to avoid contamination or moisture change. Field labeling (borehole ID, depth) and chain-of-custody records are also best practice to avoid mix-ups.

Getting a representative sample is another practical concern. Field variability means sampling should cover the area of interest. In agricultural sampling, this is handled by compositing many subsamples as described above. In site investigations, drillers may use grid or pattern sampling: for example, regulations might require boreholes in a grid so that no major landform is missed.

Within a borehole, samples are usually taken at regular depth intervals and at any visible layer change. Quality control logs often note the recovery of each sample (for instance, if a tube retrieved the full length of soil) to judge sample reliability. Some labs even X-ray or CT-scan undisturbed cores to check if they remained intact during transport.

Conclusion

In summary, disturbed and undisturbed soil sampling are two complementary approaches that serve different purposes. Disturbed sampling (using augers, spoons, or excavated material) is fast and cost-effective for obtaining chemical and classification data. Undisturbed sampling (using Shelby tubes, piston samplers, etc.) is more complex but necessary for accurately measuring mechanical and hydraulic properties.

The choice of method should always align with the project goals. Routine agronomic surveys will almost always use disturbed, composite sampling for fertility. Major construction or groundwater projects will emphasize undisturbed cores for engineering tests. The need for soil data is only growing. Advances in technology—such as automated soil samplers, in-situ sensors, and precision agriculture tools—are beginning to make sampling more efficient and data-rich.

Remote Sensing