“You can’t manage what you don’t measure” — this holds especially true in agriculture, construction and environmental science. Soil sampling is the first step toward understanding soil health and ensuring the success of any land-based project. In fact, the global soil testing market is booming: it’s projected to grow from about $4.3 billion in 2025 to $6.9 billion by 2035 (CAGR ≈ 4.9%).

Farmers, landscapers, and engineers are all seeking better data on soil nutrients, compaction, and contaminants. But with so many samplers available, how do you pick the right one?

Define Your Application & Soil Type

Soil characteristics directly affect productivity, safety, and environmental outcomes. For instance, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization reports that poor soil fertility contributes to yield losses of up to 30% in smallholder farms worldwide.

Meanwhile, geotechnical surveys show that over 50% of construction failures in developing countries are linked to poor soil assessment. Choosing the right sampler for your application and soil type is the first step toward avoiding these risks.

What will you use the samples for? Different fields require different sampler features. Consider these scenarios:

1. Agriculture & Lawn Care: Typically the goal is nutrient and pH analysis of topsoil. Farmers and gardeners often take many small cores across a field (e.g. 15–20 samples per 4–5 hectares) and mix them into one composite sample. This composite is tested for pH and key nutrients to guide fertilization. For this purpose, a simple hand probe or auger is often enough. Since the samples will be mixed, preserving soil layers isn’t important.

2. Environmental & Geotechnical: Here you may need to test for contamination, compaction, or structural stability. In environmental surveys, technicians often collect disturbed auger samples at many points to check pollutant levels, because this is fast and cost-effective.

But if you need to know how contaminants move through soil or need data on soil strength and compaction, you’ll need undisturbed cores. Geotechnical engineers (for buildings or roads) usually insist on Shelby tubes or piston samplers to get intact samples for strength and consolidation tests.

3. Research & Archaeology: Some research projects require near-perfect cores. Archaeologists, for example, use small push probes or micro-coring tools to retrieve intact soil layers without mixing them. (These tools can be very specialized, often custom-made for thin cores and cores with liners.)

Also think about soil conditions in your site:

- Soft/Sandy/Loamy Soil: Most samplers will work fine. A hand auger or push probe can penetrate easily.

- Hard/Clay Soil: You may need extra force. A weighted slide hammer or hydraulic probe helps drive the tool into dense clay. Some probes have replaceable heavy-duty tips for extra punch.

- Rocky/Gravelly Soil: Steel samplers can jam. In these soils, a slide hammer or powered drill (with rock bits) is usually required. Look for samplers with replaceable tips that can break through gravel, and hollow stems to clear debris.

When choosing, always match the tool to your soil type. For example, some push probes have narrow blades for wet soils or stainless steel tubes for abrasive soils. Compare models based on price, durability, ease of use, tip type (drill bit vs. pointed tip) and diameter to suit your conditions.

Determine Your Soil Sampling Depth

Soil depth is one of the biggest factors in agricultural and environmental testing. Studies show that nutrient concentrations can vary by more than 40% between the top 6 inches and the subsoil layer. In construction, more than 60% of foundation failures are linked to poor understanding of deep soil behavior.

This makes depth selection a crucial decision when choosing your sampler. How deep does your sample need to go? This depends on your goals:

1. Shallow (0–12 inches, ~0–30 cm): Typical for lawns, gardens, pastures or the topsoil layer of a farm field. Soil tests (pH, phosphorus, potassium) often use 6–8 inch cores. For example, many crop tests sample 0–6 inches because that’s where most roots and nutrients are concentrated. In no-till fields or pastures, labs may use 6–8 inch depth to account for residue.

2. Medium (1–6 ft, ~0.3–1.8 m): Used when you want subsoil information. In agriculture, deeper samples (e.g. 6–24 inches) can be taken for nitrate testing. In shallow groundwater or contamination surveys, probes might sample down a few feet. Hand probes can work in this range, but it gets tougher. In general, manual probes work easily to about 5–10 ft (1.5–3 m).

3. Deep (6+ ft, >1.8 m): Needed for geotechnical or very deep contamination work (e.g. testing clay layers or bedrock interface). These depths require heavy equipment like hollow-stem augers or hydraulic rigs. Hand augers become impractical beyond ~5–10 ft.

Even powered augers typically have limits (often 10–15 ft of continuous core). For very deep cores (up to 80+ ft), geotechnical drill rigs and specialty samplers (e.g. rock corers, hollow stem augers for casing) are used.

Always choose a sampler rated for at least the depth you need. Remember, taking multiple shallower samples or a single deep sample can yield different information. Also ensure you have depth stops or markings on your tool so every core is the exact same length – consistency is critical for reliable data.

Choose Your Soil Sample Type: Disturbed vs. Undisturbed

The way you handle soil cores can determine the accuracy of your results. Recent reports show that up to 25% of lab testing errors can be traced back to incorrect sampling methods. Disturbed and undisturbed samples each serve different purposes, and choosing the wrong type could lead to costly mistakes. This is a crucial decision:

Disturbed Sample: The soil is mixed inside the sampler. You break up and homogenize it (like mixing all collected cores together). This is fine for chemical tests (nutrients, pH, contamination levels) because the original soil structure doesn’t matter. Disturbed sampling (augers, large-diameter corers, or even shovels) is fast and cheap.

It’s the standard for farm fertility sampling: collect many cores in a zig-zag or grid pattern, mix them, then send to lab. The advantage is speed and low cost – you can quickly sample large areas. The downside is you can’t learn anything about soil layering, compaction or structure from a disturbed core.

Undisturbed Sample: The soil is extracted intact, keeping the layers and moisture in place. Tools like Shelby tubes, split-spoon samplers, or piston corers are used. These collect a solid core of soil. This is essential when you need physical or engineering properties (e.g. density, shear strength, hydraulic conductivity).

By preserving the sample’s natural structure, lab tests can simulate real ground conditions. The tradeoff is cost and effort: undisturbed sampling usually requires specialized equipment (often hydraulic rigs) and skilled operators.

A good rule: use disturbed (composite) sampling for routine agronomy and broad chemical checks. Switch to undisturbed (core) sampling when doing geotechnical or in-depth environmental investigations.

Select Power Method: Manual vs. Mechanical Soil Sampler

Labor efficiency has become a defining factor in modern soil sampling. With farms getting larger, demand for fast and consistent samples has grown. In North America alone, more than 60% of professional soil testing for agriculture now relies on mechanized or hydraulic sampling equipment.

Yet, manual tools remain the choice for most small-scale users due to their affordability and portability. Decide whether to go hand-powered or machine-powered:

1. Manual Samplers: These are hand-operated probes, augers or shovels. Examples include push probes (with foot treads or T-handles), hand augers, tile spades, and post-hole augers.

- Pros: Portable, simple, and affordable. No engine means you can take them anywhere and they rarely break.

- Cons: Labor-intensive and slower. It’s hard work to collect many samples manually, especially in tough soil.

Manual samplers are generally limited in depth; most work comfortably only a few feet deep. Also, human error can lead to inconsistent depth (each person pushes differently). For a small garden or a few quick cores, manual is fine.

2. Hydraulic/Mechanical Samplers: These attach to tractors, ATVs or stand-alone rigs. They include hydraulic hand-held hammers, motorized soil probes, and full direct-push rigs.

- Pros: Power and speed.

A tractor-mounted probe or robot can slam into hard clay or reach 10+ ft with ease. Depth is consistent and it’s much less tiring. High sample throughput is possible (ideal for precision ag with dozens of samples).

- Cons: Cost and complexity.

You need engines or hydraulics, fuel/battery, and sometimes custom mounts. Initial investment is higher (often thousands of dollars), and maintenance is greater. Examples: the AMS “Coresense” hydraulic coring system or Geoprobe direct-push rigs.

Bottom line: If you’re sampling a few shallow spots, a manual push probe or auger is fine. If you need to collect many cores, go deep or through hard layers, a powered drill or hydraulic probe is worth it.

Evaluate Features & Ergonomics of Soil Sampler

Comfort and efficiency are increasingly important in soil sampling. A recent survey among agronomists showed that over 45% considered ergonomics and ease of cleaning as major factors in tool selection. With repetitive sampling becoming the norm in precision agriculture, even small design differences can significantly affect productivity and user fatigue. Once you narrow it down, look at the details. Even small differences in design can affect ease of use and sample quality:

Core Diameter: Smaller tubes (1–1¼ inch) need less effort but give a tiny sample; larger tubes (2–3 inch) take bigger cores. Bigger cores can be more “representative” and reduce sample error, but they require more force and make heavier samples. For composite nutrient tests, ½–¾ inch cores are often enough. For precise work or structure tests, 2 inch+ may be better.

Material: Steel probes are common. Stainless steel is rust-resistant (good for wet soils) but heavier. Carbon steel is lighter but can corrode. Some samplers use chromoly steel for strength. Check if the sampler has a protective coating or plating.

Handle & Design: Ergonomics matter. T-handles, foot treads, and slide-hammer grips all exist. A T-handle probe gives good leverage, while some probes have pads for your foot. Slide-hammer samplers need a solid frame that won’t bend. For repetitive sampling, look for padded grips or spring-tension mechanisms.

Portability: How heavy and bulky is it? For portable use, choose lighter probes (with aluminum parts or hollow shafts). For field equipment, ensure it mounts securely. Also consider handle length (taller handles reduce back strain) and storage (do extensions break down?).

Ease of Cleaning: Soil samplers can get clogged. Tools like augers with removable flights, split tubes that open, or slide hammers (which eject the core) are easier to clean. Some push-probe kits include collapsible liners or core catchers that make retrieving the sample simpler.

Durability: Look for hardy construction if you’ll be in rocky or abrasive soils. Check reviews or specs for wear-resistant bits and hard-case options.

Types of Soil Sampler – A Detailed Breakdown

Soil sampling techniques are rapidly evolving—recent surveys show that over 65 % of large-scale agricultural operations and 80 % of geotechnical firms now use core or mechanical sampling tools rather than simple hand augers. The demand for precise, undisturbed cores has increased by 12 % per year in environmental consulting markets. With that in mind, understanding the strengths and limitations of each sampler type is more important than ever.

1. Augers (for Disturbed Soil Samples)

Augers are the classic disturbed samplers. They look like giant drill bits or bucket scoops. As they rotate, their cutting edges dig into soil and the cylinder (bucket) collects the sample. There are several styles:

i. Bucket Augers: (also called spiral or Wright’s augers) have a large, spiraling flight with a cutting edge. They can bore several feet down. They capture and retain soil in the cylinder, minimizing loss as you pull up. These are workhorses for farms, landscaping and geotech.

A bucket auger is “excellent for reaching depths of several feet and effective in loose, sandy or cohesive soils”. They are used whenever you need a good bulk soil sample (e.g. mixing nutrients) – including agriculture fields, contamination surveys, or geological exploration. The sample from a bucket auger is usually quite disturbed (mixed).

ii. Dutch/Hand Augers: These have a simpler construction (usually a single spiral or straight blades). They work well for 1–3 ft cores in softer soils. They’re lighter and easier for one person to operate. Great for garden or lawn testing. However, they tend to spit soil out as they drill (waste), so they need careful handling.

iii. Sand Augers: These have open flights and bigger gaps to gather very loose, wet, or sandy soil. They let sand fall into the flight. They are used mainly in geotechnical and environmental boring for shallow sand layers.

In general, augers are fast and general-purpose. If you need a soil sample quickly for basic analysis, an auger is usually the way to go. Just remember that the sample is disturbed. Many pros say augers provide “a high level of accuracy” and “consistent sampling” for fertility, contamination or geotech work, because they let you collect a good volume of soil even deep down.

2. Core Soil Samplers & Push Probes (for Undisturbed Samples)

Core or tube samplers are built to collect undisturbed cores. Think of a sharp thin-walled tube that gets pounded or pushed into the soil, pulling up a cylinder of intact soil inside. Examples include push probes, open-tube corers (Shelby tubes), and split-tube samplers. These preserve the soil’s layers and moisture.

i. Open-tube probes (sometimes with detachable liners) are common in turf and ag. You simply press or drive the tube to the desired depth, then pull it out and dump the contents. Split-tube samplers have two halves that clamp around the core and can be driven by a hammer.

After pulling up, you unscrew the ends to remove the soil column. The advantage is clear: you get an intact column. These are used in any case where “moisture content and structural integrity are critical” – such as contamination analysis (to preserve volatile chemicals) or soil stability tests.

In turf management or lawn care, a small diameter open probe (e.g. 3/4″ or 1″) is often enough. In geotech, Shelby tubes (~2–3″) are standard for clay soils. The image above shows various soil core sampler designs.

Core samplers are usually heavier and require more careful handling (you often seal both ends after extraction). But if you need to test for compaction, shear strength or hydraulic conductivity, an undisturbed core sampler is the right choice.

3. Slide Hammer Samplers (for Compacted Soils)

In recent field studies, slide hammer samplers reduced operator fatigue by up to 40 % and increased penetration success in compacted clay soils by 15–25 % compared to manual push probes. When soil is very hard or compacted, even driving a steel tube can be tough.

That’s where slide hammer samplers come in. A slide hammer is essentially a heavy weight (a “hammer”) that slides up and down on the sampling rod. You attach it to an auger or corer.

How it works: you place the sampler at the surface, then let the weight fall and slam down on the rod. The momentum drives the tip into the ground. You repeat this until reaching depth. The same hammer can also push up on the rod to help pull out the tool. In effect, it’s like adding a jackhammer function to your probe.

This method is very useful for medium-depth sampling (several feet) in dense clay or fill. For example, for compacted soil sampling you might attach a 1″ probe to a slide hammer to get 3–5 foot cores.

According to AMS, slide hammers are “a versatile tool for driving soil probes” and give a straightforward driving force by dropping weight. They allow you to reach greater depths in challenging soils. In practice, if a hand probe just won’t penetrate, try a slide-hammer probe: the extra impact makes it much easier.

4. Specialized Soil Samplers

Use of specialized samplers has grown by 20 % in environmental and geotechnical work over the last five years, especially in contaminated site remediation and deep core projects. Beyond the common types above, there are niche samplers for particular needs:

i. Shelby Tubes (Thin-Walled Samplers): These are thin steel tubes (2–6 inch diameter) used mainly in geotechnical work. A Shelby tube has a sharpened beveled edge and is pushed into undisturbed clay/silt to cut an intact core. They are usually driven hydraulically in a drilled hole to avoid disturbance. Shelby tubes are not hand-held tools; they need a drill rig or specialized equipment.

Use them when you need a high-quality undisturbed sample for compressibility or shear tests. (They’re often called push tubes or Acker tubes too.) Shelby tubes are ideal for fine-grained soils – just know that driving them can be hard work in anything stiffer than soft clay.

ii. Split-Spoon Samplers: A split-spoon is the classic sampler for Standard Penetration Tests (SPT). It’s a thick steel tube, split into halves, driven by a drop hammer. The soil entering a split-spoon is technically disturbed but can still be relatively cohesive.

You’ll see this used in geotech for rapid sampling of various strata. It’s not for perfectly intact cores (since the hammering disturbs the sample), but often gives a good enough core for classification and some strength estimates.

iii. Stationary Piston Samplers: These have a piston that sits at the bottom of the sampler during insertion, preventing suction. When the tube is pushed down hydraulically (instead of hammered), the piston holds the sample in place until withdrawal. The result is a very undisturbed core. Piston samplers are used in very sensitive soils where even a Shelby tube might smear.

iv. Pit-Hammer Kits: Some kits (e.g. AMS bulk density kit) include a pit hammer with a circular cutting head. By hammering and then pulling up, you extract a volumetric core (knock out a plug). This is useful if you need a precise volume (for bulk density or porosity tests).

v. Mud Augers: These augers have slots or wide flights to handle wet, sticky soils. If you’re coring in saturated clays or swampy ground, a mud auger (with cut-outs in the tube wall) helps remove the heavy clay. They often have plug valves or extra openings so you can empty the clay out easily. In plain terms: for saturated or clay-rich sites, use a mud auger to avoid clogging.

Each of these specialized samplers is chosen for particular field conditions. For most soil sampling tasks, you’ll pick among the more general categories above, but keep these in mind if you hit sticky or silty soils, or need exact-volume cores.

Leading Soil Sampler Companies & Options

The soil sampling equipment market has been growing steadily in recent years, driven by demand for precision agriculture, environmental monitoring, and infrastructure projects. According to a 2024 market report, the global soil testing equipment sector is projected to reach $6.9 billion by 2035, expanding at nearly 5% CAGR from 2025 onward.

Much of this growth is fueled by rising adoption of smart farming, government regulations for land use, and the need for accurate soil data before construction. As this demand increases, a handful of companies dominate the market with specialized tools that cater to farmers, agronomists, and engineers worldwide. If you’re ready to buy, here are some top brands and what they’re known for:

1. AMS (Art’s Manufacturing & Supply)

A fourth-generation family business (est. 1942) specializing in soil sampling tools (ams-samplers.com). They offer everything from basic push probes and augers to hydraulic systems. AMS is often cited as an innovation leader.

Options: They produce simple hand probes, augers, slide hammers, and advanced systems like the AMS PowerProbe.

Precision Features: AMS hydraulic samplers such as Coresense are designed for high-volume sampling and can be mounted on tractors or utility vehicles. These machines are GPS-compatible, making them highly useful for zone sampling in precision agriculture. Consistent depth control ensures reliable data across entire fields.

Why It Matters: If you are managing hundreds of acres, AMS gives you both portability and power. Their samplers reduce human error and ensure your samples line up with precision maps.

2. Clements Associates Inc.

Clements focuses strongly on agriculture and environmental sampling, building tools that are both durable and accurate. Clements probes are often air-lifted or pneumatic, allowing 30+ foot depths.

Options: Their most famous products are the JMC Environmentalist Subsoil Probe and Enviro-Safe Samplers.

Precision Features: These tools are widely used in grid and zone sampling, which are essential for precision farming. Many agronomists pair Clements probes with handheld GPS units, ensuring they take samples from the exact same locations year after year. This repeatability is critical for tracking soil fertility over time.

Why It Matters: Clements is an excellent choice for professional agronomists or consultants who need reliable probes for long-term soil monitoring.

3. Wintex

A Canadian company making rugged manual samplers. Wintex gear (and related brands like Radius) are known for all-steel durability. If you need simple, sturdy tools for any soil type, Wintex is a popular choice. Their slide hammers and T-handle probes are built for rough use.

Options: They manufacture push probes, manual augers, and hammer-driven samplers.

Precision Features: While Wintex tools are mostly manual, they are often paired with GPS devices or farm management software to record exact sample locations. This makes them useful for smaller farms adopting precision techniques without heavy investment in machines.

Why It Matters: Wintex provides durability and affordability. Their samplers are simple but can fit into precision workflows when combined with GPS tracking.

4. Falcon

Falcon is more focused on geotechnical and environmental investigations rather than agriculture. They also sell pit-hammers and block samplers. Geotechnical engineers often order Falcon equipment when they need regulatory-quality soil cores.

Options: They are known for Shelby tubes, piston samplers, and U100 dynamic sampling kits.

Precision Features: Falcon’s tools don’t come with built-in GPS, but they are often integrated into environmental workflows where GPS mapping and remote sensing are used to guide drilling locations. Their specialty lies in providing undisturbed soil cores for construction and contamination studies.

Why It Matters: Falcon is the go-to choice for engineers who need deep, undisturbed samples to assess building sites or environmental risks.

5. Oakfield Apparatus

A Nebraska-based company making quality manual samplers at a friendly price. Oakfield’s focus is on straightforward, easy-to-use probes and accessories (like sample bags and liners) – a great choice for gardeners or entry-level users.

Options: They make stainless steel push probes, soil tubes, and accessories like sample bags.

Precision Features: Oakfield tools are fully manual, but they can easily be used with GPS logging apps to record where each sample is taken. While they don’t have built-in precision features, they are often used on small farms, turf management projects, or gardens where cost is a factor.

Why It Matters: Oakfield is ideal for hobbyists, gardeners, and smaller farms. Their probes are lightweight, durable, and easy to clean.

6. Geoprobe Systems

Geoprobe Systems leads in mechanical direct-push rigs (they actually make full drilling trucks). Their machines can drill and sample in one go. Geoprobe is a leader in heavy-duty sampling rigs, often mounted on trucks or trailers.

Options: They produce direct-push rigs and hydraulic coring systems capable of deep and high-volume sampling.

Precision Features: Geoprobe rigs can be combined with GPS guidance and remote sensing maps, making them highly effective for environmental studies and advanced site investigations. Their equipment ensures accuracy and speed on large projects where dozens of deep cores are needed.

Why It Matters: Geoprobe is best suited for engineers, large farms, and government projects where both depth and volume of samples are critical.

7. Spectrum Technologies

Spectrum bridges traditional soil sampling with digital technology and sensors.

Options: They provide soil probes, moisture meters, and nutrient testing kits.

Precision Features: Spectrum specializes in combining soil samplers with real-time sensors. Their tools are often paired with remote sensing data, allowing farmers to match lab results with drone or satellite imagery. This creates a stronger picture of soil health and crop performance.

Why It Matters: Spectrum is perfect for farmers and researchers who want to integrate soil sampling directly into data-driven precision agriculture systems.

Each of these brands has its niche. For example, AMS and Clements gear can be seen on big farms and research projects. Wintex and Oakfield gear is everywhere on smaller farms and environmental sites. Falcon is a go-to for engineers. When choosing a brand, consider not just price but support, parts availability, and local distributor networks.

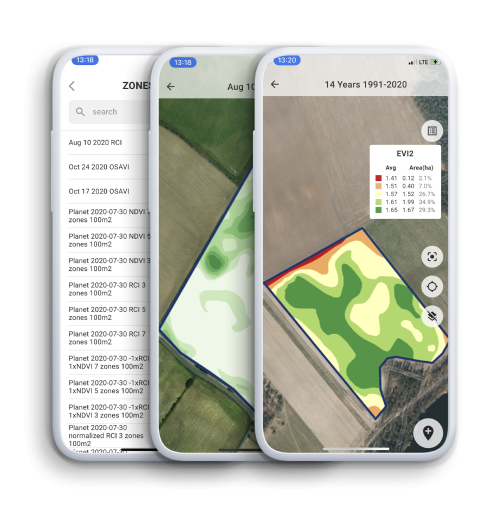

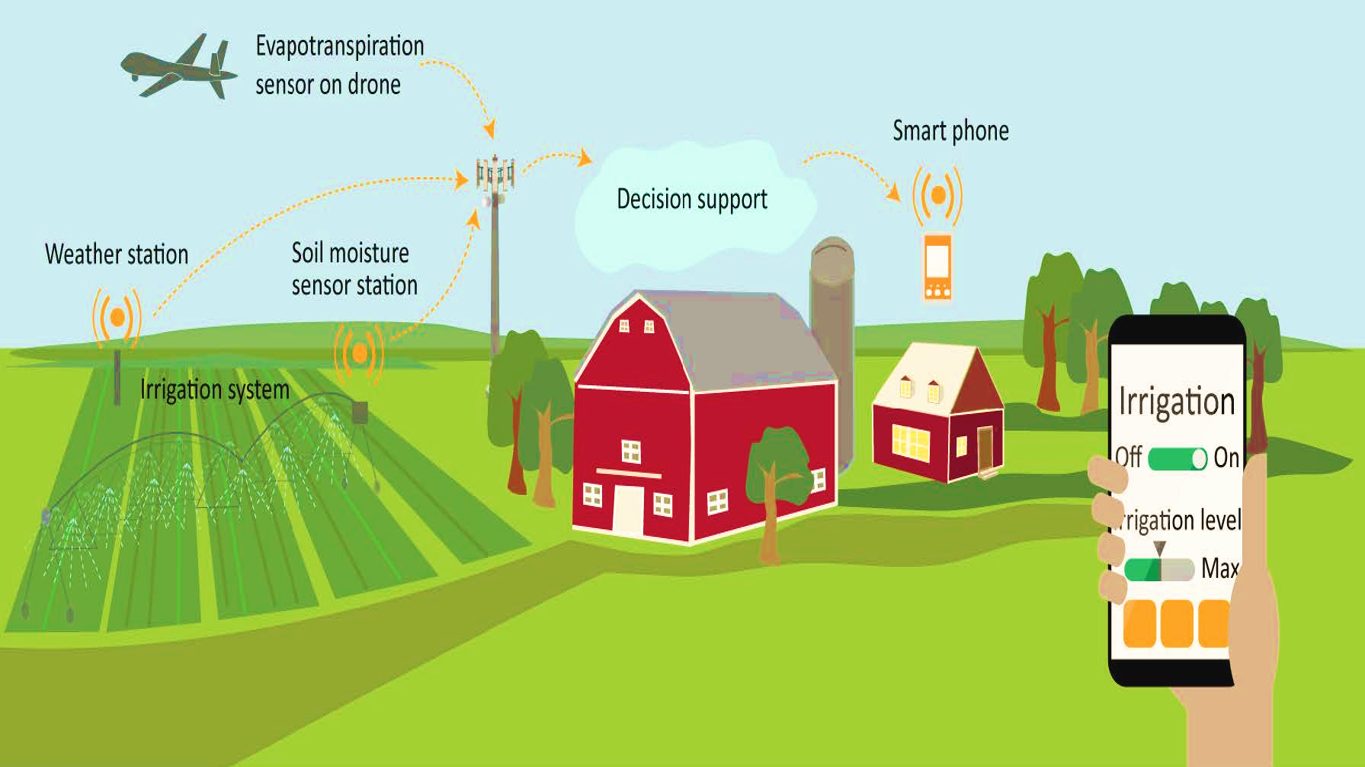

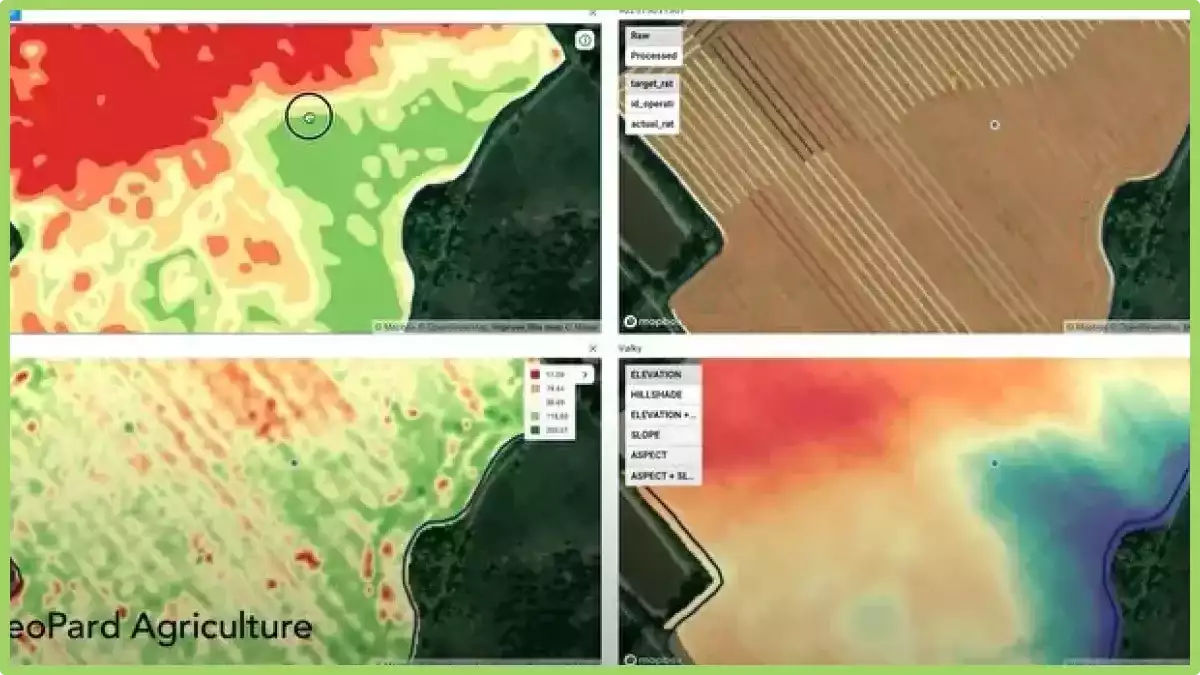

The Modern Context of Precision Ag, Remote Sensing & Soil Sampler

The global precision agriculture market is expected to grow from $9.7 billion in 2024 to $16.4 billion by 2030, at a CAGR of about 9.2%, driven by the need for accurate, data-based farm management. Soil sampling is a critical piece of this growth, as more than 80% of large-scale farms in North America and Europe now use GPS-guided soil sampling methods.

Studies show that precision soil sampling can reduce fertilizer costs by up to 20% while increasing yields by 5–15%, making it one of the most cost-effective practices in modern farming. In recent years, technology has transformed soil sampling. Farmers and scientists now combine satellites, drones, GPS and robotics with old-school tools. Here’s what’s changed:

1. From Blanket to Zone Sampling

In the past, many fields were sampled as a single unit (“blanket sampling”). Today, precision agriculture breaks fields into management zones. Using satellite imagery, drone maps or yield monitors, agronomists identify areas of similar productivity or soil type. Then each zone is sampled separately. For example, instead of taking one composite sample per 40 acres, a farmer might sample one composite per 10-acre zone.

Grid vs. Zone Designs: There are two main designs. A grid pattern (e.g. every 2–5 acres) treats each grid cell equally. This can map fine-scale variation but can be costly if done at high density. A zone-based approach divides the field by soil color, yield history or slope, and samples each zone. Zone sampling can give “almost the same accuracy as grid sampling” with fewer samples.

Remote Sensing: Tools like NDVI (crop vigor), EM soil conductivity, and yield data create maps of variability. Now, soil labs often receive georeferenced samples. As one study puts it, a yield map or NDVI map can identify “high/medium/low productivity areas” which become separate sampling zones. This targeted approach improves efficiency. It was found that nutrient levels can vary up to 40% within the same 10-acre zone! By sampling according to this variability, a farmer avoids “hidden” problem spots.

In practice, a precision workflow is: remote sensors flag areas of concern (the “Where”), and then a team or robot physically samples those zones to find out “What” is really in the soil. This method yields far more actionable data than one-sample-per-field.

2. How Technology Changes Sampler Requirements

Higher sampling intensity and accuracy demand better tools:

Speed & Volume: If you’re taking 20+ cores per field, manual methods may be impractical. Many precision ag professionals use hydraulic or automated samplers. For instance, AMS’s tractor-mounted Auto-Field Sampler (AFS) or a soil-sampling robot can grab dozens of cores in the time a person could do a few. Modern equipment often features vacuum lines or spring-loaded ejection to dump the core quickly.

Depth Consistency: When sampling many points, you need identical depths. Advanced probes use depth collars or sensors. Robotic samplers like ROGO’s system even achieve ±1/8″ depth accuracy. They “learn” from each core and adjust force so each core is exactly the same length. Look for tools with clear depth markings, stops or feedback controls.

GPS-Guidance: Today’s samplers usually integrate GPS. Some handheld probes have mounts for a GPS receiver, while automated systems use RTK-GPS guidance. For example, ROGO notes that with RTK GPS they can “repeat sample locations precisely from year to year.” On simpler budgets, a phone or tablet with mapping apps can also guide your route across a zone. Always record each core’s coordinates.

Data Logging: New samplers may even log data digitally. After each sample, a button press can tag it with an ID and location. Some systems interface directly with farm management software. The key is that each soil core becomes ground truth tied to a specific field zone.

Durability for Field Use: As sampling becomes higher-stakes, companies are building tougher samplers. Look for robust frames, sealed bearings on slide hammers, and metal connections that resist wear. In short, modern precision ag demands consistent, repeatable tools — not just occasional probes.

3. The Data-Driven Workflow

Putting it all together, here’s how many precision farms operate:

- Identify Zones: Use satellite/drone imagery or yield maps to create management zones. Each zone should be relatively uniform or address a known issue (e.g. a low-spot, or a drainage area). This is your map of “where” to sample.

- Plan Sampling Points: Decide how many cores per zone (commonly 15–20) and at what depths (e.g. 0–6″ and 6–24″). Use GPS or marked flags to space out the points evenly. Many growers walk in a zig-zag or “W” pattern across each zone.

- Collect Samples: Using your chosen sampler and method, collect each core. Keep the depth constant, and avoid any bias (e.g. don’t always sample near roads). If collecting composites, put all cores from a zone in one bucket and thoroughly mix them. (Studies show using 15–20 cores per composite can reduce sampling error by ~90% compared to only 5 cores.)

- Document Everything: Label each sample with field, zone, depth and GPS coordinates. Even FAO reports note up to 30% of lab errors come from poor labeling or handling.

- Lab Analysis: The lab sends back detailed data (pH, nutrients, contaminants). Because each sample has location info, you now have a map of soil properties.

- Precision Application: Finally, this information feeds into variable-rate equipment. You might apply lime or fertilizer differently in each zone, or dig down deeper only where contamination is flagged.

Conclusion

Choosing the right soil sampler comes down to a few core questions: Why am I sampling, what kind of soil am I dealing with, how deep do I need to go, what type of data do I need, and how will I collect it? By answering these, you can quickly match a sampler to your project. For hobbyists and gardeners, a simple push probe or hand auger—like Oakfield’s stainless steel model—offers an affordable and durable way to check shallow soil conditions. It’s easy to use and perfect for quick tests in gardens and lawns.

Professional agronomists benefit most from mechanical probes or hydraulic systems. Tools like the Clements JMC or AMS hydraulic corers save time, improve consistency, and work seamlessly with GPS guidance for precise fertility mapping across large fields. Geotechnical engineers, on the other hand, need undisturbed samples. Shelby tubes and split-spoon samplers from Falcon or AMS are industry standards, often paired with hydraulic rigs for deep, accurate cores essential to construction and environmental studies.

No matter who you are, the right sampler will unlock accurate soil insights. With this guide, you now have the confidence to choose the right tool and begin uncovering the story beneath your land.

Remote Sensing